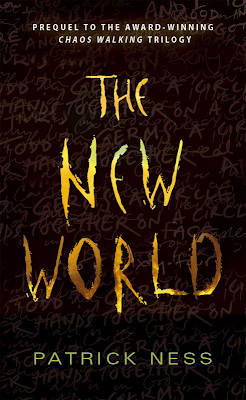

There is something comforting in the blend of obviously young adult and obviously ultra-light science-fiction that author Patrick Ness crafts for "The New World" (2009), a prequel (of sorts) to some trilogy of books he wrote. Those weren't free, "The New World" was, and as the first novel checks in at close 500 pages, chances are they are not going to be read by me in the next decade. Also, as Ness has a couple of writing conceits that would surely bother me in longer form, I think I did both he and I a service by reading the short story instead.

Would this have been better if it weren't so ridiculous in its premise – that the vanguard for settling an alien world is a single ship occupied by a mother, father, and (now) 13 year old daughter? No. It needs that mix of camp, improbable, almost teenage angst, and danger to frame the story. Not that there is much to the story. Girl and her parents have to go live on the alien planet by themselves for a few months so that when the thousands of others arrive, there is some worthwhile intelligence about the place and – believe it or not – maybe a place cleared for settlement and agriculture. Of course, most adults would have sent a far larger group, certainly more than one advance ship, but to the mind of a young adult (10-14 is my estimate for the real audience for this type of writing) it makes perfect sense. That is how things are done, right? The family unit is inviolate (until the parents destroy it, but even children who have witnessed that likely yearn for the fiction of a family being a unit that cannot be divided).

It appears that the protagonist of "The New World" does appear in the trilogy, and maybe some of the background information given here plays into her adventures later on. A lot of it feels forced, but would undoubtedly satisfy the younger crowd as seeming plausible. For as much information as Ness wanted to put into this prequel, I was surprised at how little he developed the information he was giving. He names the ships in the interstellar convoy – at least some of them – but doesn't note how many there are. He has those people who are awake for the journey acting as "caretakers" to those in some kind of cryo-sleep, but there doesn't seem to be much caretaking as just learning how to work on the ships and learning about what to do if they ever reach the planet. There are two cats on one of the ships (which begs the question of the role of the cats and why are there only two – are they done with them or is there no concern about habitual inbreeding in the pet population?).

I would like to take a brief moment to wonder why YA fiction has become so lengthy. Not this short story, of course, but the trilogy runs over 1600 pages. I just read William Golding's Lord of the Flies (1954), and the most popular printing of it reaches 208 pages. Catcher in the Rye (1951) – definitely not one of my favorites – is less than 300 pages. Now, those are considered literature but they are really bucking at the edge (if not much closer to the center) of the YA audience and concerns. I've never read S.E. Hinton's The Outsiders (1965), but it is another work that doesn't feel the need to fill close to or more than 500 pages; like Golding's book, it is done at 208 pages. It seems to me there has been some sort of notion foisted upon young readers – and I know this is not new – that reading a longer book makes you a better reader. A lengthy book certainly makes one commit to it, sure, but I think I would have rather been reading Golding, Hinton, and Robert Heinlein's Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) than commit to reading Stephen King's It (1986) – no offense to the seriously successful classmates who were King devotees and counted It and Pet Semetary (1983) as their big reading accomplishments for junior high.

I guess that is my ultimate point. There are YA (or near YA) titles that are considered honest to God literature. One should probably read those before indulging with things like Ness' trilogy on "The New World". Because it is in reading the better works – and I would leave Salinger out of that, but I would probably be wrong – that we, as an audience, come to realize that there should be something more than just an unfolding story in what we choose to read. (Incidentally, a charge that has been made against me as an author is that I often don't have any kind of plot or story in my pieces, in which case one should definitely read Ness before reading me.)

No comments:

Post a Comment