From the outset, Howard Zinn makes it clear (both through his own voice and that of Matt Damon) that it is his job to take issue with the state of the world. It is his responsibility as a teacher, he notes before the title credits appear, "to intercede in whatever is happening in the world". Zinn believes that the power structure (presumably in the world, definitely in the United States of America) has been set up improperly and has unfairly disadvantaged the decent and hardworking while rewarding the corrupt and greedy.

In a passage taken from his book (You Can't be Neutral on a Moving Train, 1994), Zinn decries the Protestant Work Ethic and presumption that hard work will lead to success (Zinn purposely misunderstanding the possibility of hard work leading to riches for the guarantee of it to better frame his argument). Zinn is a markedly better writer than a speaker -- he too often repeats himself in succession, he struggles to find simple words to express his point -- but in what the audience is exposed to here, it is not at all clear that he is worldly or wise. His concept of the world seems to be largely forged from his childhood experiences, his anger (aroused by the abuses, excesses, and exploitations of American capitalism) seems too broadly spread , and his sense of self-importance/self-congratulatory paranoia speaks more of a man still looking to be validated (or lauded by those who endorse his views). His zeal is not without merit; it is in fact excellent that there are people like Zinn who go beyond the reasonable in their (self-appointed) defense of the common man, the workers, the citizens who actually constitute the body politic, because they are the ones who stir us from our complacency with our lot, with the status quo.

The film does a good job showing the evolution of Zinn's awareness (though the absolute naïvité with which he begins seems unbelievable, almost cartoonish and for effect) as to the political, social, and economic divides in the country. It also shows Zinn's lack of intellectual curiosity; he is interested in events that relate to his upbringing, his past, his experiences, and is surprisingly easily brought into line with the orthodoxy (if such a thing can be said) of labor movement's radical side. He places himself at the forefront of events, strategically rearranging the facts to fit his narrative (an example: he begins teaching at Spellman College in 1956, but identifies that as being before the Civil Rights Movement instead of in the early years of said movement).

It is not surprising that Zinn would find himself involved (on the right side) with the Civil Rights Movement. It is not surprising that (for valid reasons of earnest and honest self-reflection or intellectually immature, self-aggrandizing reasons) he would find himself involved in the peace movement (against the war in Vietnam). The film does a decent job of showing Zinn's involvement and his (lasting) influence. It does a fantastic job of showing where he is either ironically correct ("The best way to make sure that a country turns to communism is to put foreign military forces in it", a policy the Soviets definitely used in expanding Communism) or (will later be proven to be) factually wrong (stating that the conflict in Vietnam was driven by internal forces or that the Viet Cong were part of an uprising against the South Vietnamese government -- when in fact they were a part of the North Vietnamese army and were themselves, in a manner of speaking, foreign troops in their own native country).

I have the same problem with Zinn that I do with Thoreau. They both expend a tremendous amount of intellectual energy to end up with arguments that have already been attended in 'modern' philosophy (which is to say that the intellectual arguments appear very immature, but Zinn is appealing to emotion and 'moral outrage' as much, if not more, than reason). This is not to say that Zinn doesn't have a point. Of course he does, and we are better represented as a people for his repeated and passionate presentations of his worldview. But it is not well-rounded enough to be considered reliable. He wants to avoid the whitewashing of history and that is most admirable. Zinn wants to present the stories that history had, in the past, judged to be the dissent that could be omitted. He does not appear to lay claim to the totality of history; he is not asking or attempting to censor other representations of how we came to be as a nation. The sides he is representing are the ones that have been ignored. His dedication to them is not an omission of other foci -- there is no shortage of the opposing points of view.

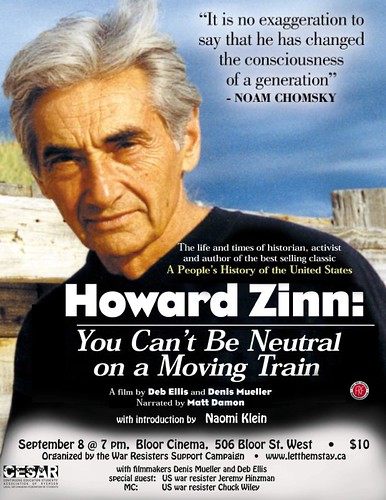

I would imagine the fan of Zinn would find little more here than a nice personal warmth to associate to the voice on the page. Those who would demonize him and his causes will only be infuriated. Howard Zinn: You Can't be Neutral on a Moving Train (2004) didn't instill any greater desire for me to read Zinn, nor did it lessen it. It serves as a pleasant, short overview of Zinn's life and work. He comes off as likable, for the most part. His points have a degree of positivity and hope that is often lacking in those made by people speaking for the opposition, if sometimes served up with a hefty amount of hyperbole.

No comments:

Post a Comment